With the upcoming release of Metal Gear: Revengeance and the announcement of Metal Gear Solid: Ground Zeroes, Grant got to thinking about his history with the series.

November 2001. In a dingy, cold bedroom, I am huddled up in a blanket next to a three-bar electric heater. I am 14 years old, and I am playing Metal Gear Solid for the first time. I am holding my controller in one hand and the multi-plug strip that powers the console in the other and I am staring wide-eyed and terrified at the screen like it is about to draw a gun on me.

Metal Gear Solid was borrowed from a friend, and despite reading about the revolutionary title in a 1998 copy of Computer and Video Games magazine, I didn’t know anything about it. I wasn’t prepared for the torture sequence.

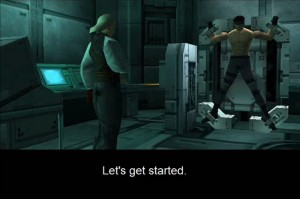

Snake, the lead character, is strapped into an electrical torture device operated single-handedly (snerk) by professional mercenary and career dickhead Revolver Ocelot. The player has to tap Circle to resist the torture – and tap it a lot, too, for too long. In a move Heavy Rain would repeat over ten years later, the act of input became so uncomfortable that it underlined the actions onscreen.

Snake, the lead character, is strapped into an electrical torture device operated single-handedly (snerk) by professional mercenary and career dickhead Revolver Ocelot. The player has to tap Circle to resist the torture – and tap it a lot, too, for too long. In a move Heavy Rain would repeat over ten years later, the act of input became so uncomfortable that it underlined the actions onscreen.

I wasn’t prepared for the idea that a single failed action could change the rest of the game and see an important character killed. I’d grown up with games that used lives and continues, of course, but these weren’t devices of narrative failure. In canonical terms, Mario made it to the final castle and rescued the Princess. If you died, that’s you getting the story wrong. That didn’t actually happen. Games like Prince of Persia and Assassin’s Creed (and even MGS 3) deal pretty cleverly with the weirdly elastic narrative structure of games, but for the most part, the “truth” behind a game’s story lies in a perfect playthrough.

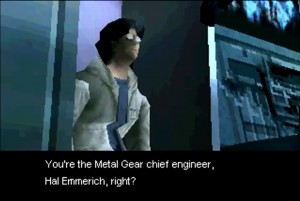

But then, the torture. Failure to resist the electrocution means that you sell out Meryl, your contact at the base, resulting in her death and a relatively minor (but still pretty emotional) change to the storyline – at the end of the game, you escape with Otacon, a nerd who hides in lockers and pees himself at the first sign of a one-eyed cyborg ninja hefting a four-foot power sword. If you fail during the sequence, there are measurable consequences that you carry around with you for the rest of the story – it’s not that it’s the wrong story. It’s the right story, and it’s the story of you being a weak-willed coward who sold out your contact because you couldn’t push circle fast enough.

Or it’s the story of the time that you died and couldn’t play any more because if you died on the torture rack you died for good – there are “no Continues,” as Ocelot says directly to the fourth wall. I didn’t know what that actually meant. Presumably it just makes you reload your save – but back then, it could have been the end of the game. It might have wiped all my data. I didn’t know.

The first time I got wind of what was about to happen I got so spooked at the enormity of the decision that I turned off the machine. I wasn’t ready for this. I wasn’t suddenly ready for a life without Continues which barred me from casual experimentation and forced me into sudden, difficult action.

I went online. (I dialed up, to give you an impression of how advanced our internet was in 2001) I went to Gamefaqs and scrolled through reams and reams of plain text documents until I found the bit about the torture. It wasn’t lying. No-one said what happens if you die, as though no-one had dared to try. I left the console alone for the rest of the night and went to bed, scared.

The next night, I prepared myself. My fourteen-year-old heart thumped in anticipation. The controller sat on my right thigh, the power strip on my left. Should I fail the torture and die, I would flick the power off with my left thumb (it stood poised over the on/off switch on the strip, one that I’d borrowed from behind the TV in the lounge for tonight only) before whatever hideous fate the game had in store could take effect.

There was no question of ever giving up Meryl.

I started up the game, and I sat through the cutscene again more out of fear than actually listening to the characters waffle on and then I pushed that circle button like no-one’s ever pushed it. I pushed it like a man runs out of a burning building. I pushed it like a man struggling for air, pulled under water by riptides. I pushed it like I was holding back a barbarian horde from knocking through giant wooden doors.

I started up the game, and I sat through the cutscene again more out of fear than actually listening to the characters waffle on and then I pushed that circle button like no-one’s ever pushed it. I pushed it like a man runs out of a burning building. I pushed it like a man struggling for air, pulled under water by riptides. I pushed it like I was holding back a barbarian horde from knocking through giant wooden doors.

Middle finger outstretched, index finger resting on top, entire arm tensed into pain, I pushed. I won. Snake survived. Meryl lived. I got a bandana for my troubles that inexplicably game me infinite ammunition as long as I wore it.

It’s all a bit silly, really, considering that my plan to outsmart the PS1 was to turn it off and reload from my previous save, which is pretty much exactly the same thing I would have had to do if I’d failed. But I’m happy that I did. I’ll never forget that cocktail of fear and excitement.

Kojima’s strength as a designer and director comes from a definite feeling that he’s right, I think. Throughout the many, many Metal Gear Solid games it’s clear to see all the little ideas and quirks that have been left in where other developers or publishers would have seen them ironed out to speed up production or ensure a broader appeal for the game. In Metal Gear, they’re all allowed to sit and flourish and play together.

Kojima’s strength as a designer and director comes from a definite feeling that he’s right, I think. Throughout the many, many Metal Gear Solid games it’s clear to see all the little ideas and quirks that have been left in where other developers or publishers would have seen them ironed out to speed up production or ensure a broader appeal for the game. In Metal Gear, they’re all allowed to sit and flourish and play together.

That’s not always a good thing, as the length of his cutscenes show – but in the nooks and crannies of game-design, it works. Without that, there wouldn’t be the ludicrous range of close combat moves, or the two-minute ladder climbs, or the slipping on birdshit, or the hidden codec streams, or the torture sequences that are scary because they attack the player, not the protagonist. Kojima’s games aren’t perfect, but those details stay with you.

With the upcoming release of Metal Gear: Revengeance and the announcement of Metal Gear Solid: Ground Zeroes, Grant got to thinking about his history with the series.

November 2001. In a dingy, cold bedroom, I am huddled up in a blanket next to a three-bar electric heater. I am 14 years old, and I am playing Metal Gear Solid for the first time. I am holding my controller in one hand and the multi-plug strip that powers the console in the other and I am staring wide-eyed and terrified at the screen like it is about to draw a gun on me.

Metal Gear Solid was borrowed from a friend, and despite reading about the revolutionary title in a 1998 copy of Computer and Video Games magazine, I didn’t know anything about it. I wasn’t prepared for the torture sequence.

I wasn’t prepared for the idea that a single failed action could change the rest of the game and see an important character killed. I’d grown up with games that used lives and continues, of course, but these weren’t devices of narrative failure. In canonical terms, Mario made it to the final castle and rescued the Princess. If you died, that’s you getting the story wrong. That didn’t actually happen. Games like Prince of Persia and Assassin’s Creed (and even MGS 3) deal pretty cleverly with the weirdly elastic narrative structure of games, but for the most part, the “truth” behind a game’s story lies in a perfect playthrough.

But then, the torture. Failure to resist the electrocution means that you sell out Meryl, your contact at the base, resulting in her death and a relatively minor (but still pretty emotional) change to the storyline – at the end of the game, you escape with Otacon, a nerd who hides in lockers and pees himself at the first sign of a one-eyed cyborg ninja hefting a four-foot power sword. If you fail during the sequence, there are measurable consequences that you carry around with you for the rest of the story – it’s not that it’s the wrong story. It’s the right story, and it’s the story of you being a weak-willed coward who sold out your contact because you couldn’t push circle fast enough.

Or it’s the story of the time that you died and couldn’t play any more because if you died on the torture rack you died for good – there are “no Continues,” as Ocelot says directly to the fourth wall. I didn’t know what that actually meant. Presumably it just makes you reload your save – but back then, it could have been the end of the game. It might have wiped all my data. I didn’t know.

The first time I got wind of what was about to happen I got so spooked at the enormity of the decision that I turned off the machine. I wasn’t ready for this. I wasn’t suddenly ready for a life without Continues which barred me from casual experimentation and forced me into sudden, difficult action.

I went online. (I dialed up, to give you an impression of how advanced our internet was in 2001) I went to Gamefaqs and scrolled through reams and reams of plain text documents until I found the bit about the torture. It wasn’t lying. No-one said what happens if you die, as though no-one had dared to try. I left the console alone for the rest of the night and went to bed, scared.

The next night, I prepared myself. My fourteen-year-old heart thumped in anticipation. The controller sat on my right thigh, the power strip on my left. Should I fail the torture and die, I would flick the power off with my left thumb (it stood poised over the on/off switch on the strip, one that I’d borrowed from behind the TV in the lounge for tonight only) before whatever hideous fate the game had in store could take effect.

There was no question of ever giving up Meryl.

Middle finger outstretched, index finger resting on top, entire arm tensed into pain, I pushed. I won. Snake survived. Meryl lived. I got a bandana for my troubles that inexplicably game me infinite ammunition as long as I wore it.

It’s all a bit silly, really, considering that my plan to outsmart the PS1 was to turn it off and reload from my previous save, which is pretty much exactly the same thing I would have had to do if I’d failed. But I’m happy that I did. I’ll never forget that cocktail of fear and excitement.

That’s not always a good thing, as the length of his cutscenes show – but in the nooks and crannies of game-design, it works. Without that, there wouldn’t be the ludicrous range of close combat moves, or the two-minute ladder climbs, or the slipping on birdshit, or the hidden codec streams, or the torture sequences that are scary because they attack the player, not the protagonist. Kojima’s games aren’t perfect, but those details stay with you.

Share this: