Games are playing it safe. They need to become more challenging. Not challenging in terms of difficulty but they need to challenge the way we think.

Games are playing it safe. They need to become more challenging. Not challenging in terms of difficulty but they need to challenge the way we think.

Years ago, I had an argument with someone who said that our favourite films couldn’t be the “best” films because for a film to be your favourite it had to be easy to watch. I disagreed with him at the time, but there is something to be said for films that mess up your brainpan and leave you feeling unsettled, rather than just happy. Films that stick with you for days or weeks afterwards as you struggle to fit together the pieces, fascinated by a story that’s uncomfortable and just out of reach. Great films should be challenging.

And now, games. Games aren’t pushing these same buttons. How many times have you walked away from a game with that same worm of curiosity digging away in your belly, that leaves you thinking about the plot and characters the next morning while you eat breakfast? I’m betting not that often.

Games need closure by their very nature. They’re interactive challenges, and as they ask the player to push through difficulty (and not just watch the characters do it) they need tight cycles of risk and reward to ensure play. Feedback, in other words, can’t afford to be ambiguous. Even games like the superlative Amnesia: The Dark Descent, a title shrouded in mystery hinted at but rarely ever seen, has a system where the main character regains sanity after completing an objective.

Games need closure by their very nature. They’re interactive challenges, and as they ask the player to push through difficulty (and not just watch the characters do it) they need tight cycles of risk and reward to ensure play. Feedback, in other words, can’t afford to be ambiguous. Even games like the superlative Amnesia: The Dark Descent, a title shrouded in mystery hinted at but rarely ever seen, has a system where the main character regains sanity after completing an objective.

Players need to feel in control. They need to feel as though their efforts mean something in the game story; whether that’s a cut-scene at the end of a level, a new set of abilities unlocked through XP, or simply an achievement popping up onscreen offering the digital equivalent of a pat on the head.

Plus, mystery is hard to sustain when you give a character full control. Let’s say, in a film, a character witnesses a murder but can’t make out the identity of the person involved. They don’t especially want to risk their lives, so they hide until everything blows over and are consumed with guilt. In a game? You’ve got save points, so there’s no fear of death. Run after the murderer! Can’t catch them? Crack open the console and pop in a noclip cheat so you can run through the walls to cut them off, and find them standing motionless in a room you were never meant to see or watch them wink out of existence as their time in the story finishes.

So it’s hard, then, to maintain an atmosphere that disturbs and intrigues players when they have access to the whole virtual set and feel upset when they’re asked to not look behind the painted sack-cloth. A couple of games have managed it, though.

Like Spec Ops: The Line, a game with a storytelling style so revolutionary that it’s informing everything I write at the moment. A game which uses the mechanics of third-person shooters to perform a damning critique of third-person shooters, and the representation of war as a whole. Not only does it upset the player and wrong-foot them at every turn, but it draws them through the story even as they’re becoming scared of the man that they’re controlling. When I finished it, I had to go outside for a cigarette and stare directly forwards for around half an hour. I had to come to terms with what I’d done, even though none of it was real. None of it was even realistic, but the story touched on so much so strongly that it left a mark.

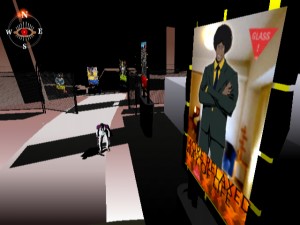

Then there’s the other end of the spectrum with Suda 51’s auteur titles, most notably Killer7. I’ll admit I didn’t have the first clue what was going on with Killer7 until I read an online plot synopsis, and even then, it wasn’t terribly clear.

Then there’s the other end of the spectrum with Suda 51’s auteur titles, most notably Killer7. I’ll admit I didn’t have the first clue what was going on with Killer7 until I read an online plot synopsis, and even then, it wasn’t terribly clear.

But that chap’s a master of the in medias res, starting stories in the middle of a conflict and letting you patch the details together as you go. Why are these people all part of the same fractured mind? What’s going on with those invisible giggling genderless suicide bombers? How come ghosts keep talking to me, and why is every tutorial delivered by a gimp hanging off the ceiling?

There’s no time to find out, and no answers are given until you’ve invested plenty of time into the setting and characters. It’s easy enough to be “random” and jam ridiculous collections of stuff into games hoping to get a laugh on the same level as a madlib, but for incongruous elements to not only mesh in an interesting way but to continually hint at a hidden meaning takes real talent.

And almost coming entirely out of the realm of games is The Stanley Parable, a first-person adventure that makes you question every game ever. It’s astonishing stuff and if you’ve not played it, it’s free so you don’t really have an excuse. You can download it through Steam for literally nothing and play through all of it in the space of about an hour, and it’ll shake the way you follow orders and seek out objectives much in the same way Bioshock did but six times over in the space of your lunchbreak.

[Spoiler Alert] An example: at one stage, in one of the endings, you end up in a giant room set to self-destruct. The narrator tells you that there’s nothing you can do to escape.

[Spoiler Alert] An example: at one stage, in one of the endings, you end up in a giant room set to self-destruct. The narrator tells you that there’s nothing you can do to escape.

You find a series of buttons located all over the room that respond when you push them, so you push them because you’ll try anything to fix the problem of the exploding room, and the narrator says “I bet you’re pushing all those buttons, aren’t you? They don’t do anything, you know.” And they don’t. [End Spoiler]

The thing that unites these games, though, is that they’re not very good as standalone games. If you strip the story away from Spec Ops, you have a passable third-person action game. If you examine Killer7, you end up with a frustrating on-rails shooter. And the Stanley Parable… well, it’s not supposed to be good. It’s meta.

They’re all worth playing, though, even though that as mechanical challenges, as a set of ducks at a fairground, they’re not great. They show what games can be once you get past the idea that players have to be continually pulled along by the nose through balanced challenges and rewards. They’re only going to become rarer as the industry deals with the recession, seeing middle-sized studios forced out of business and replaced with scrappy indie underdogs and AAA behemoths, which is sad.

We need to be challenged. We need our favourite medium to tell stories that mess us up and keep us on our toes, rather than just washing over us in a sea of cover-based combat and predictable plot twists. We need games that aren’t be afraid of being bad for the sake of being good.

Years ago, I had an argument with someone who said that our favourite films couldn’t be the “best” films because for a film to be your favourite it had to be easy to watch. I disagreed with him at the time, but there is something to be said for films that mess up your brainpan and leave you feeling unsettled, rather than just happy. Films that stick with you for days or weeks afterwards as you struggle to fit together the pieces, fascinated by a story that’s uncomfortable and just out of reach. Great films should be challenging.

And now, games. Games aren’t pushing these same buttons. How many times have you walked away from a game with that same worm of curiosity digging away in your belly, that leaves you thinking about the plot and characters the next morning while you eat breakfast? I’m betting not that often.

Players need to feel in control. They need to feel as though their efforts mean something in the game story; whether that’s a cut-scene at the end of a level, a new set of abilities unlocked through XP, or simply an achievement popping up onscreen offering the digital equivalent of a pat on the head.

Plus, mystery is hard to sustain when you give a character full control. Let’s say, in a film, a character witnesses a murder but can’t make out the identity of the person involved. They don’t especially want to risk their lives, so they hide until everything blows over and are consumed with guilt. In a game? You’ve got save points, so there’s no fear of death. Run after the murderer! Can’t catch them? Crack open the console and pop in a noclip cheat so you can run through the walls to cut them off, and find them standing motionless in a room you were never meant to see or watch them wink out of existence as their time in the story finishes.

So it’s hard, then, to maintain an atmosphere that disturbs and intrigues players when they have access to the whole virtual set and feel upset when they’re asked to not look behind the painted sack-cloth. A couple of games have managed it, though.

Like Spec Ops: The Line, a game with a storytelling style so revolutionary that it’s informing everything I write at the moment. A game which uses the mechanics of third-person shooters to perform a damning critique of third-person shooters, and the representation of war as a whole. Not only does it upset the player and wrong-foot them at every turn, but it draws them through the story even as they’re becoming scared of the man that they’re controlling. When I finished it, I had to go outside for a cigarette and stare directly forwards for around half an hour. I had to come to terms with what I’d done, even though none of it was real. None of it was even realistic, but the story touched on so much so strongly that it left a mark.

But that chap’s a master of the in medias res, starting stories in the middle of a conflict and letting you patch the details together as you go. Why are these people all part of the same fractured mind? What’s going on with those invisible giggling genderless suicide bombers? How come ghosts keep talking to me, and why is every tutorial delivered by a gimp hanging off the ceiling?

There’s no time to find out, and no answers are given until you’ve invested plenty of time into the setting and characters. It’s easy enough to be “random” and jam ridiculous collections of stuff into games hoping to get a laugh on the same level as a madlib, but for incongruous elements to not only mesh in an interesting way but to continually hint at a hidden meaning takes real talent.

And almost coming entirely out of the realm of games is The Stanley Parable, a first-person adventure that makes you question every game ever. It’s astonishing stuff and if you’ve not played it, it’s free so you don’t really have an excuse. You can download it through Steam for literally nothing and play through all of it in the space of about an hour, and it’ll shake the way you follow orders and seek out objectives much in the same way Bioshock did but six times over in the space of your lunchbreak.

You find a series of buttons located all over the room that respond when you push them, so you push them because you’ll try anything to fix the problem of the exploding room, and the narrator says “I bet you’re pushing all those buttons, aren’t you? They don’t do anything, you know.” And they don’t. [End Spoiler]

The thing that unites these games, though, is that they’re not very good as standalone games. If you strip the story away from Spec Ops, you have a passable third-person action game. If you examine Killer7, you end up with a frustrating on-rails shooter. And the Stanley Parable… well, it’s not supposed to be good. It’s meta.

They’re all worth playing, though, even though that as mechanical challenges, as a set of ducks at a fairground, they’re not great. They show what games can be once you get past the idea that players have to be continually pulled along by the nose through balanced challenges and rewards. They’re only going to become rarer as the industry deals with the recession, seeing middle-sized studios forced out of business and replaced with scrappy indie underdogs and AAA behemoths, which is sad.

We need to be challenged. We need our favourite medium to tell stories that mess us up and keep us on our toes, rather than just washing over us in a sea of cover-based combat and predictable plot twists. We need games that aren’t be afraid of being bad for the sake of being good.

Share this: