Indie Rock: Cart Life and Dys4ia: Empathy Through Reality

- Updated: 23rd Jan, 2013

There’s a category making a debut at this year’s Independent Games Festival (IGF) awards. The 15th annual ceremony that takes place during Game Developers Conference (GDC) will, along with accolading quality independent games for a variety of other reasons, see the first “Excellence in Narrative” honour handed out.

Whoever’s picking the winner out of the five nominated would have to be a daredevil maverick who constantly sleeps with a gun under their pillow and one eye open. A rebel who flips off authority with both hands, but damn it, they get results.They’d have to be, it’s a tough category. Every single name within it is a great example of what gaming can achieve in storytelling, not just because of the quality of what’s being told, but because of how each pick adeptly uses the medium of gaming in order to do so.

I couldn’t tell you whether or not 30 Flights of Loving is better than Kentucky Route Zero: one eschews all player knowledge of context and allows for discovering implied subtext without sacrificing their ability to traverse the environment; one directly involves the player in authorial ownership of the story without adapting the events at all. I couldn’t deny Gone Home the win either, partially because narrative told in reverse through finding objects scattered around is an incredible use of the form, but mostly because I haven’t played it at all yet and shouldn’t bother to offer my opinion.

Instead, what I’d like to do is tell you why the toughest pick of the whole list is between Dys4ia and Cart Life, since they’re two of my all-time favourite games for exactly the same reason, despite being so disparate in their attempts and content.One’s short, one’s long, one tells a single story, the other sets up a framework wherein others can be told, one contains a solely neon colour scheme and the other is totally monochromatic. Both are real experiences made just a fraction more fantastical.

Cart Life is based loosely on people that the creator Richard Hofmeier knows just trying to make it through life while also trying to set up and run a business. Dys4ia however, is an autobiographical story about developer Anna Anthrophy’s experience going through hormone replacement therapy.

What these two do is use gameplay in order to foster empathy. Cart Life presents experiences that we all go through: governmental bureaucracy, plans falling apart, thinking you know what you’re doing until something throws a spanner in the works, forgetting appointments, not eating right and even losing track of time.

The game does all this through systems that allow for emergent situations to unfold as a result of what you do and don’t achieve. It overwhelms you in an attempt to make you feel just as helpless as the character you’re controlling. In your own life you likely don’t know how to do everything in order to be the person you want to be; the game makes you feel at one with the character by throwing too much at you to deal with and giving you too little time to do it.

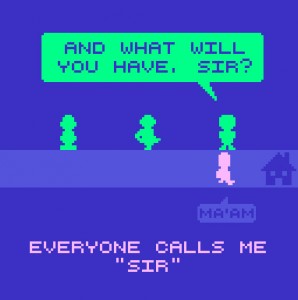

Dys4ia is much more simple. It tells a short linear story that maybe the majority of players will never go through, but by doing so gives them a better understanding than just having been told. You don’t live Anna’s Experience, yet by having a connection to it you know what she went through and you’re better able to contextualise the events through interaction.

It reminds me of the way that Adam Atomic’s Press Any Key tries to get the player to connect with the reality of a situation through gamification. Press Any Key starts by tallying up your button-taps until you reach a particularly high number, then informs you that the purpose is to make you type out as many keystrokes as there were casualties during the Iraq war up until the day of release. It allows you to have context through action rather than being informed of a statistic and not truly having it register.

The way that Dys4ia and Cart Life respond to player failure is nearly unique, as there isn’t any. You can definitely not do well, but in both games everything carries on and it becomes an anecdotal part of the experience. Cart Life allows for new experiences to emerge, whereas Dys4ia uses failure as an end-state to the activity you’re performing and move on to the next one; it makes failure as relevant an end to the situation as it would be in real life.These are two games that make the player really understand. They’re two games that use the medium of gaming to produce a feeling impossible through any other artistic method. These are two incredible games that, unfortunately, can’t both win an award they each truly deserve.

Follow Us!